Microbial pond life in an icy desert

The second of my 16-week research projects undertaken as a part of my MRes was based at the Natural History Museum (NHM), London. I was working with samples of microbial mat communities from meltwater ponds in Antartica, arguably one of the weirdest habitats on earth.

The McMurdo Ice Shelf in Antartica forms a 50m thick undulating surface of ice floating on the sea. Annual summer thawing of ice and snow causes the formation of thousands of ponds in depressions on the ice. Variable amounts of trapped marine sediments and salt are released from the ice as it melts. This results in ponds which are very close together in space and yet at opposite ends of the spectrum in terms of salinity and pH. They can vary in size from thousands of meters in diameter to two, and have assorted levels of ice cover.

The meltwater ponds of the McMurdo Ice Shelf are colonised by microbial mats, one of the few things that can survive in these extreme environments. Microbial mats are one of the earliest signs of life found on earth, thought to have been present 4,000 million years ago. They owe their persistence to their co-operative nature. The mats are actually composed of lots of different kinds of micro-organisms, organised into a multi-layered, three dimensional sheet. Each layer contains organisms with a different functional role. There are oxygen- and sun- loving cyanobacteria in the upper layers gradually giving way to anaerobic and sulphate- loving bacteria at the lowest levels, with many other groups in-between. The cyanobacteria at the top convert sunlight into energy and the waste products of the organisms at each layer are then food for the layer below them.

In this study, we wanted to understand how the extreme environments of the meltwater ponds might shape the microbial mat communities residing in them.

My supervisor, Anne Jungblut and her collaborator, Ian Hawes, had spent a field season in Antartica and returned with six frozen microbial mat samples from six meltwater ponds and measurements of pH, conductivity (a measure of salinity) and temperature from each.

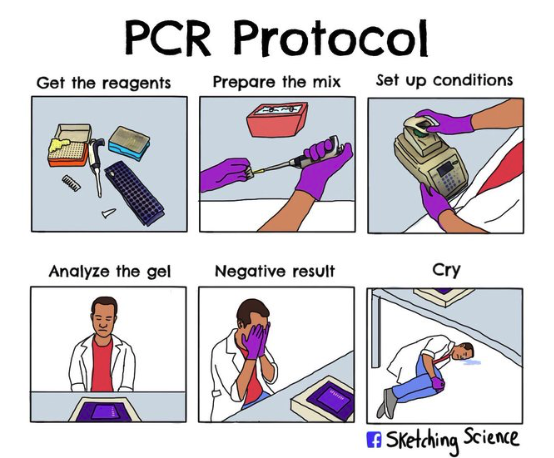

To find out what was living in the mats we had to extract DNA from each sample and amplify it (via PCR) ready for sequencing. This involved lots of shiny high-tech equipment and many failed attempts.

Weeks of hard work were condensed down into 550 nano grams of PCR product in very tiny test tubes and sent to the NHM sequencing facility. After a nail biting wait, we were rewarded with reams of DNA sequence data. Matching our data to a database of known DNA sequences for different organisms, we were able to determine the community composition of each of our microbial mat samples.

This was the first time eukaryote communities from these habitats had been analysed, and we collected more samples than had been used in previous studies, enabling us to look at heterogeneity within each pond for the first time.

We found that communities from different ponds were all quite different from each other. Mats from the saltiest pond and the most acidic pond were especially different from the others. We also saw that these two ponds, which were at the extremes, had lower species diversity and richness. Different communities taken from the same pond were very similar. Taken together, these results could be suggestive of environmental filtering.

Environmental filtering happens when species arrive at a location but are unable to persist there due to aboitic conditions. So, while some species are able to exist in ponds just few meters away, the extreme salinity of a neighbouring pond may prohibit them from establishing there.

The findings from this study will further our understanding of processes that sustain biodiversity in ice-based habitats, which is especially important with the acceleration of environmental change that may accompany future, and current, polar warming. Understanding biodiversity in extreme environments can also provide us with a window into the past. Some of the oldest recognisable Precambrian fossils are of laminated cyanobacterial mats. The communities we have characterised here, may not be so different to those that existed in the early days of life on Earth.

Read the paper here